Art News NZ: Grace Wright, Pure Energy

Taking cues from Western art history and Eastern spirituality, from music and dance, painter Grace Wright wants her audience to experience the harmony of a higher plane while remaining grounded in the body. Nansi Thompson speaks to her.

“I’m constantly working to paint the inconceivable,” says Grace Wright. “After the mounting chaos of gestural agony suspends us, the moment gravity shifts before the fall is where the painting lies. This gap where everything falls away and we are back in the body is a hidden harmony – and by experiencing it, we transcend it.”

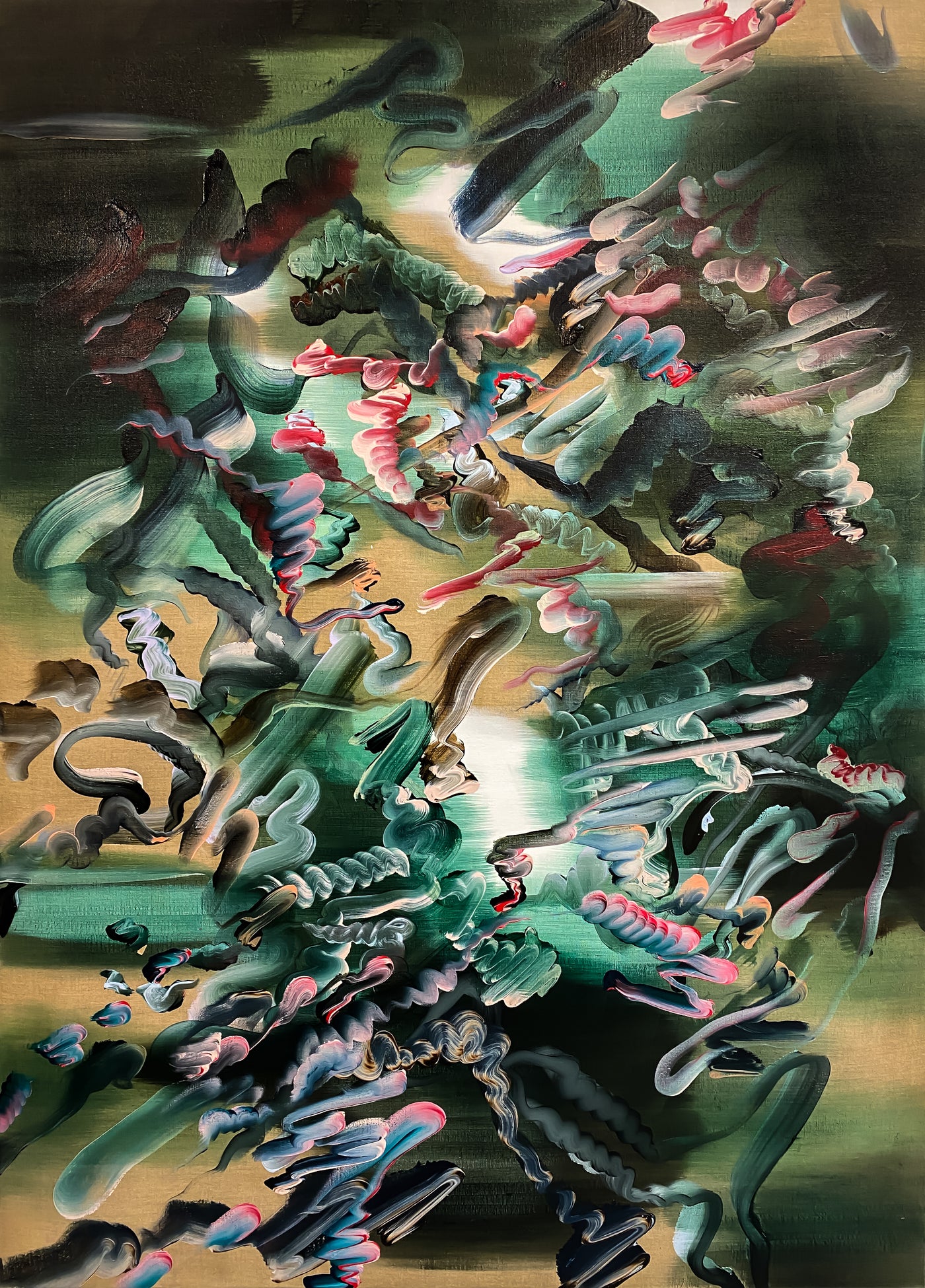

Alpha Paradise – an exhibition of large abstract landscapes begun during the lockdown – sees Wright and her work move into turbo-shift. Exploding along with the spring, this is a monumental exhibition. Brushstrokes sweep, gather and unfold, or disperse fat, gestural cherubs across dramatic colour fields. The grand narratives of the Renaissance are here under a cosmic upgrade, in abstracted sci-fi fantasy and video game glory.

Wright’s painting style has evolved with distinct and satisfying shifts. During 2019, her final year of an MFA at Elam School of Fine Arts, the artist’s earlier, more graphic works gave way to looser and larger paintings. She began to experiment with different techniques: fat brushes swept horizontally; curving brushstrokes unfurled as far as the paint would go; edges diffused; and massive paintings rotated in 180-degree shifts, shuffling their logic. Former abstracted images of the body expanded to convey the sense of being a body. In works such as The Night Mist of My (Tangerine) Heart (2019), a viewer can feel the tense probing and trailing of Wright’s ultrasound wand. Wright’s work was speaking to “an inherent bodiliness”.

In Alpha Paradise the intestinal clusters are now more sprung. Released trails cascade, reverberate and echo in open space. The unbleached linen she stretches for her paintings grounds the brushstrokes; it absorbs and darkens the forest greens, browns, and other brooding tonals, or lies naked in the midst of the drama. Under some transparent dark layers, darker gestures gestate. But there are also large swathes of horizontal fluoro magenta, lapis lazuli, cerulean blue, primrose yellow and pops of pure white. Surfacing colours flicker and astonish, in thick pastels tinged with pure colour. This is chiaroscuro pushed to an abstract edge.

Alpha Paradise is Wright’s solo debut with Gow Langsford Gallery. The exhibition went ahead on 9 September without an opening-night gathering, due to Level 2 restrictions. It didn’t really matter: all but one of the works had sold already. Wright’s earlier exhibitions You and Your Resolve at The Vivian in Matakana last year and Fantasia for a Late Night at Parlour Projects in Hastings in March–April attracted a similar appetite. Wright also had a solo exhibition in February at Gallery 9 in Sydney, where her work was described as “a quiet manifesto on painting the dynamic”.

I ask Wright what is behind her most recent shift to pure energy.

“I think the shift into expansiveness came about for two reasons, one conscious and one unconscious. I wanted to push this concept of the paintings as landscapes. I intensified the layering and visual depth within them, evolving this idea of fantasy tableaux, or a grand narrative in which the whole narrative unfolds within the one frame.

“However, I think the second reason is due to a certain kind of reality that this year brought. The word I keep thinking of is ‘realism’. In the past, the work has always felt optimistic, but now the paintings have more forceful energy. While I was grateful for the slower pace of the lockdown and the ability to reflect, there was a shift in our experience of time. I felt as if I was treading water, that real life had stopped, and we had entered a kind of alternate reality. I was hyper-aware of the natural world and the cycles of each day. Nature seemed stronger, brighter, and I was so aware of the stillness when we weren’t continuously moving through space.

“It felt like a strange paradox, because while nature felt more forceful and ever-present, our method of interacting became more digital as we resorted to working and socialising through screens. A kind of fantasy settled over us. This indirectly came through in my last body of work – the reality of the situation dialled down any playfulness the previous work had. This is where the colour influence happened, too, in the way the colours of the ocean and the sky were kind of metallic silvers, blues, pinks and lilacs, yet these were also the colours I was seeing through my screen.”

Coming as a viewer to these works, it is not only the eye that ‘sees’. Standing in front of works like Rhapsody for a Flower (2020) it seems perfectly logical to surrender to synaesthesia and smell its colour. In that perfume, where does my own edge end? This is rather symphonic stuff and Wright is not proposing cosmic answers. Yet she is openly dancing with big questions, and her paintings hold their complexities with ease. Rather than give us respite, they deliver us from chaos by embodying it.

I spent six years in Kyoto and have lived in Hong Kong as well, which must influence my perception. When I first saw the painting Final Fantasy (2020), I felt the presence of celestial dragons, like those embroidered extravagances on the backs of kimonos, breathing and writhing between this world and the next. In the eastern tradition a dragon is an embodied spiritual force rather than a monster to be slain. Knowing that Wright has travelled in Japan, I wonder what she thinks of this reading.

“I love this reading and others have commented on it too. While I feel more formally influenced by Western traditions of painting, I do set out to capture a kind of embodied spiritual force that sits between this world and the next, as you describe. This ‘force of nature’ comes from ideas that originate in Eastern spirituality, such as the cyclical nature of time, the birth and death of formations, and the formless beneath this – I think this is what I’m trying to visualise. I find it difficult to describe with words, but while my work seems chaotic, it’s trying to develop a language of logic that somehow rhymes with these concepts. With each painting I’m trying to visualise a kind of internal logic – a language that stimulates a felt bodily response when sharing physical space with these works.”

Symphonic, harmonic, echoing and reverberating – the musical quality in Wright’s paintings is notable. Wright comes from a very musical family and studied piano seriously from childhood, until a few years ago when formal exams gave way to the rigorous demands of painting. Nowadays, she plays bass in a band with her sister, listens to Brahms in her studio and is also a dancer. These multiple creative contexts seem to play out across her stretched linen megascreens, grand as frescoed ceilings.

By offering a portal to the intangible without erasing the lived experience of the body, Wright seems to be “recasting heaven”, as a title of one of her 2019 paintings suggests. Her explorations in the direction of the ‘spiritual’ in art – an epically tricky minefield – started with a conversion of sorts. Wright tells of travelling to New York in 2015 to see works by contemporary German artist Albert Oehlen at the New Museum. She returned to the show several times. Sitting for an hour or so in front of his large-scale paintings she experienced an expanded potential for painting.

“As I stood before Born to Be late and More Fire and Ice, both monumental paintings from the 2000s, they exploded with violent colour and gesture. There was a quiet vibration beyond the inexhaustible bursting forth that I struggled to name. A hum that, as a viewer, made me feel so small, yet simultaneously arose an awareness of my own body in space. I became witness to some invisible force field, fighting its way out of the canvas; before such scale and ecstasy of gesture it felt like taking communion.”

Wright began to explore the spiritual in painting. Already drawn to the history paintings of the Renaissance and the Baroque, and the overwhelming scale of paintings such as Leonardo’s Last Judgement, she was equally observing of the ways abstract art has enabled transcendence. Her master’s essay, “Opening the earth through a glass ceiling: spirituality and the contribution of women artists in abstract painting”, highlighted the power, erasure and self-censure of abstract artists who were women. These were artists such as Hilma af Klint (1862–1944), whose mind-altering paintings received their first major American exhibition in the 1980s and who has (finally) been recognised as one of the first abstract artists.

“The art world is more religious than we might assume,” she says. “It is an ecosystem built upon a set of beliefs in the power of materiality and ideas to transcend beyond their simple mental and physical properties. By maintaining a sense of scepticism, art can have the power to hold open the world and invite new meaning that allows truths beyond our own to exist.”

This article was first published in Art News New Zealand Summer 2020.